GitHub & Collaboration

Git & GitHub

Although the terms Git and GitHub are often used interchangeably, they are two distinct tools that work together.

Git is an open-source version control system that individual users install on their local computer. It tracks every change you make to the files in a specified folder (called a repository) and acts like a time machine allowing you to go back to any previous version, see what changed, when it changed, and who made the change. Git is the most widely used version control system in the world, with an estimated 90–95% of professional software development teams using it today.

GitHub is a cloud-based platform, owned by Microsoft, that allows you to store your Git repositories online, making it easy to collaborate with others over the internet. You can think of GitHub as the Google Drive or Dropbox of your code files, but with additional tools for teamwork and project management that extend the use of Git from individuals to entire teams. Developers use Git on their local machines and push their files and subsequent changes to GitHub when they’re ready to share or back them up online. Product Managers and other collaborators can then review, comment on, and track progress through the GitHub web interface.

The Four Sections of the Git/GitHub Workflow

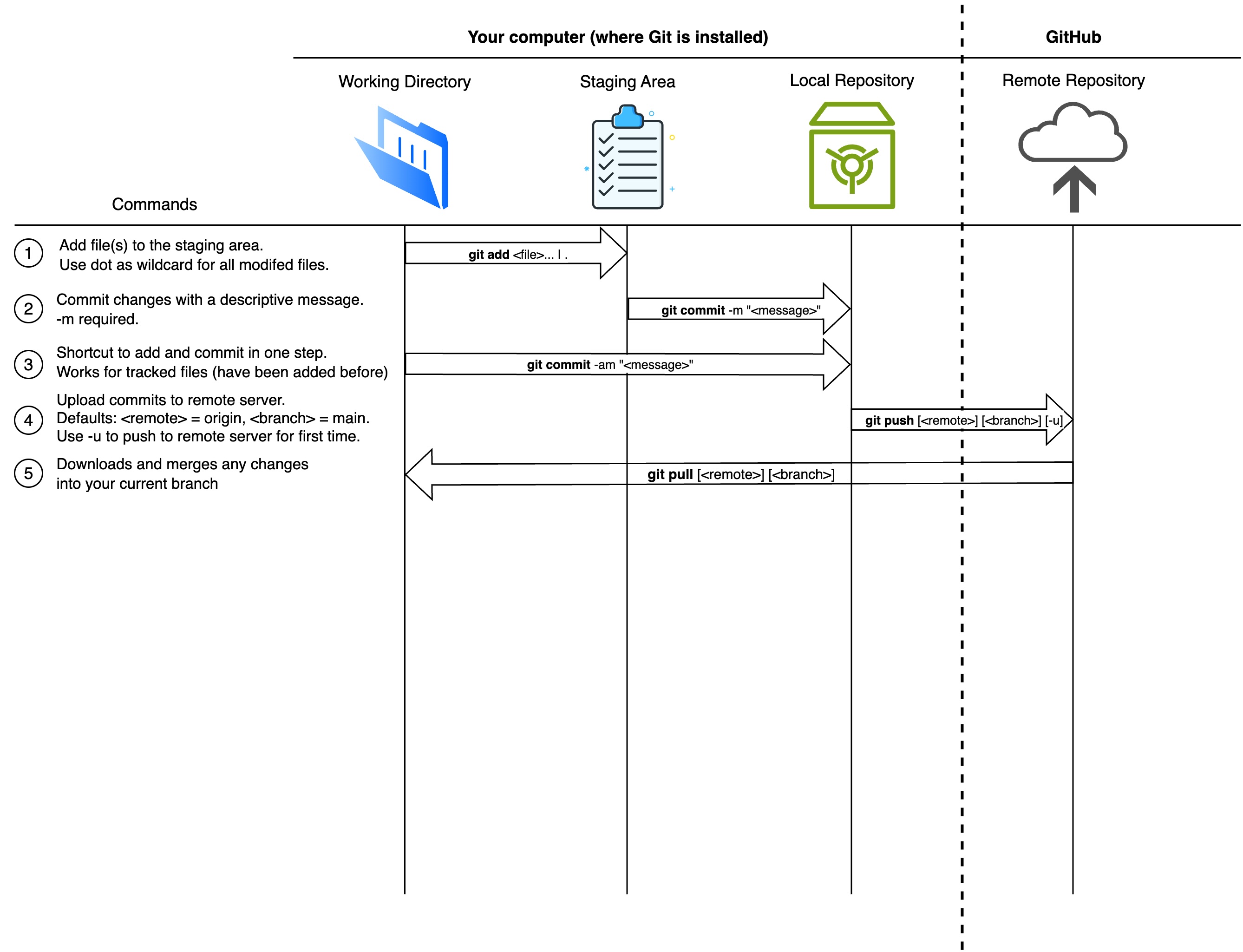

A typical workflow in get consists of editing files in your working directory, staging them, which just means listing which ones you want to save, saving or committing them and lastly, pushing them to a remote cloud hosted folder for others to use.

1. Working Directory

The Working Directory is the folder on your computer where you’re actively making changes to files such as writing code, editing documents, or creating new files.

A Working Directory is just a regular folder you’re already familiar with, the kind you see in Windows Explorer or Mac Finder.

2. Staging Area

The Staging Area is a place where you catalogue (or “stage”) the edited files from the Working Directory that you want to include in your next snapshot (version) of your project.

Each snapshot is called a commit, and the Staging Area lets you choose exactly which edited files will be saved in the next official version of your project.

Even if you’ve edited, say, 5 files, you may only want to include 3 of those changed files in your next commit. The Staging Area is where you make these choices, it gives you control over what gets saved and when.

You may hear the Staging Area referred to as the index because that’s the technical name Git uses internally for this part of the system.

3. Local Repository

The Local Repository is the part of Git on your computer that stores the official history of your project: all the snapshots (commits) you’ve made so far.

When you commit (i.e., Save) changes from the Staging Area, Git saves a permanent version of those changes in your Local Repository. This allows you to go back in time, review past versions, undo mistakes, or see who changed what and why.

You can think of the Local Repository as your personal project archive that keeps track of every meaningful step in your project’s development.

Unlike the Working Directory, the Local Repository is not a folder you typically see in Finder or Windows Explorer, rather, it lives inside a hidden folder named .git. Git uses the hidden .git folder to store all your commits as well as other project related information. It is possible to unhide the .git folder and browse it like a normal folder but many of the files are not human readable since they are designed for Git’s internal use and may look confusing or cryptic to most users.

Even though the files in the .git folder aren’t meant to be read directly by humans, Git commands allow you to retrieve any saved snapshot of your project and restore files in their original, human-readable form.

So the local repository contains everything from your Working Directory that you chose to stage and then commit.

Think of the .git folder as a vault of your project’s history. You can’t really read the vault contents directly, but Git gives you keys (commands) to retrieve and restore anything you’ve ever committed.

4. Remote Repository

The Remote Repository is a copy of your Local Repository that is stored on the internet using a platform like GitHub.

It contains the same kinds of commits and project history as your Local Repository, but it’s shared with others, which makes it perfect for collaborating with teammates, backing up your work, or deploying projects.

Your Local Repository is your personal copy, just on your computer.

The Remote Repository is the shared copy in the cloud that you and your team keep in sync.

Illustrating the Workflow

The illustration below helps you visualize the four parts of a Git workflow.

The most fundamental unit in Git is a repository, often called a repo for short. A repository is a special folder that contains all the files related to your project, along with the metadata Git uses to track the full history of changes.

The best way to

Git and GitHub Operate on a Four-Level Hierarchy

Git and GitHub organize your project using a four-level hierarchy, each building on the one below:

Level 1 – Files

These are the individual files in your project, most commonly plain text files containing code (like .py, .html, or .js), but other file types such as images (.png, .jpg) and data files (.csv, .json) are also supported and commonly used.

Level 2 – Commits

A commit is a snapshot of your entire project at a specific point in time. Git stores the exact state of all tracked files when you make a commit. Each commit has a unique identifier called a hash (e.g., f04e112) that lets you reference or return to that version.

The word commit can be both a noun (“This commit broke the build”) and a verb (“I’m committing my changes”), meaning to save a snapshot of the current state of your project.

Level 3 – Branches

A branch is a named reference (a pointer) to the latest commit in a line of development.

HEAD is a special pointer that tracks where you are in the Git repo.

Most of the time, it points to a branch name (like main or feature-x). In special cases, HEAD can point directly to a commit, putting you in a detached HEAD state.

A branch is a pointer to the most recent commit in a line of development. Because each commit remembers its parent, this pointer implicitly defines a sequence of commits — the branch’s history.

A is a label (or pointer) to a single commit — specifically, the tip (latest commit) of a line of development. Git doesn’t store branches as separate sequences of commits. Instead:

The branch points to the most recent commit. That commit points to the previous commit. And so on, forming a linked list of history. Developers use branches to work on features or bug fixes in isolation. Most repositories have a default branch called main (previously called master), which typically represents the production-ready version of the code.

When you check out a branch, Git updates your working directory to reflect the latest commit on that branch. You’re not editing that commit itself — instead, you’re preparing to build on top of it. Any changes you make and commit will be saved as a new commit, extending the history of the branch.

Level 4 – Repositories

A repository (or repo) is the top-level container that holds all your project’s files, commit history, branches, and metadata. It’s essentially your entire project, tracked and version-controlled. Repositories can live on your local computer (with Git) or be hosted online (e.g., on GitHub) for sharing and collaboration.

🔍 What Exactly Is in a Git Repository?

A repository (or repo) in Git is the full structure that stores:

Commits: Snapshots of the project’s file state over time Branches: Named pointers to specific commits Tags: Named, static pointers to commits (usually used for releases) Refs: Internally, all pointers (branches, tags, HEAD) are stored as refs Blobs: File contents (each version of each file) Trees: Directory structures (which files go in which folders) HEAD: A special ref pointing to your current working location Configuration: Repo settings like remotes, ignore rules, hooks, etc. So yes: a Git repo is the container for all of this — your entire project, including its full history and structure.

Summary

| Level | Concept | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Files | The individual contents of your project |

| 2 | Commits | Snapshots of the project at specific points in time |

| 3 | Branches | Timelines of commits used for parallel development |

| 4 | Repositories | The full project container with history and structure |

This structure can be visualized as follows:

Although they’re often mentioned together, Git and GitHub are not the same thing.

Repositories: The Project Container

A repository (or repo) is your entire project — like a folder that holds all your code, history, and collaboration tools. If you’re writing a novel, the repository is the whole book project, including every chapter, draft, and note you’ve ever made.

On your computer, a Git repo is just a regular folder with special tracking enabled. On GitHub, it’s a shared version of that folder hosted in the cloud where others can see, clone, or contribute.

Branches: Versions You Can Work On Separately

The Four Main Conceptual Areas in Git

Here’s a complete, beginner-friendly framework:

Working Directory The actual files and folders on your computer that you’re editing. What you see in your file explorer or code editor. Untracked or modified files live here. 👉 You can change files freely here, but Git doesn’t track them until you stage or commit them.

Staging Area (a.k.a. Index) A preview of what will go into your next commit. You use git add to move changes from the working directory to the staging area. Think of it like a “shopping cart” of changes you’re getting ready to commit. 👉 This gives you fine-grained control over what goes into each commit.

Local Repository Where your commits live on your own computer. When you run git commit, you move changes from the staging area into your local repo. This is the full version history that Git manages in the .git directory. 👉 You can make lots of commits locally without pushing anything to the cloud.

Remote Repository A shared copy of your repository hosted online (e.g., on GitHub). You use git push to send commits from your local repository to the remote. You use git pull or git fetch to bring changes from the remote down to your local repo. 👉 Enables collaboration, backups, and deployment.

The primary purpose of a branch in Git is to give a human-readable name to a commit, so you don’t have to use the full hash.

Why Branches Exist in Git

- Commits Are Identified by Hashes Every commit is named by a SHA-1 hash like:

Branches Are Named Pointers A branch (like main, feature-x, or fix-bug-7) is a named reference to a commit. As you commit, the branch name moves forward to the new commit.

main → commit A → commit B → commit C refs/heads/main → abc123 → def456 → 9a3e6c2

🧭 What a Branch Really Is

A branch is just a label (a file inside .git/refs/heads/) that contains a commit hash. Example:

cat .git/refs/heads/main Might output:

9a3e6c2bd8c2fb4f09f7bbfe42f27f3853fccc60 That’s it. A branch is literally a text file with a hash in it.

As you commit, the branch “moves forward” automatically

Detached HEAD mode means that HEAD is pointing directly to a specific commit hash, not to a branch.

What Is Detached HEAD Mode?

In normal Git use:

HEAD → main → commit abc123 In detached HEAD mode:

HEAD → commit abc123 ← no branch involved This happens when you check out a commit directly:

git checkout abc123 Now you’re no longer “on a branch.” You’re just sitting on a specific commit.

🎯 Why Is This Useful?

You might enter detached HEAD mode when:

You want to test or explore an old version without changing any branches You want to build something temporary, like a patch or debug run You’re checking out a tag (tags also point to commits) ⚠️ Gotcha: What Happens If You Commit in Detached Mode?

You can still make commits, and Git will let you — but:

They’ll be “floating” — not attached to any branch If you switch branches afterward, you could lose them unless you create a new branch from that point

A commit is the fundamental unit in Git. Branches, tags, and HEAD are just labels or pointers to commits. Let’s unpack it a bit more clearly:

🧱 Commits: The Core Building Blocks

Every commit: Has a unique SHA-1 hash Stores a snapshot of the project Links to its parent(s), forming the project history All real data lives in the commit graph Without any branches, Git would still work — you’d just need to use hashes to refer to everything. 🏷️ Branches: Named Pointers to Commits

A branch is a label that moves as you add commits Think of it as a bookmark: main → commit ABC123 📌 HEAD: The “Current Position” Pointer

HEAD is just a pointer to: A branch (e.g., main) → which points to a commit Or directly to a commit (in detached mode) 📷 Tags: Static Pointers to Commits

A tag is like a permanent label (e.g., v1.0) Unlike branches, tags don’t move 🧠 Mental Model

[Commit A] ← [Commit B] ← [Commit C] ↑ main, HEAD Commits = data Branches/tags = labels HEAD = where you currently are

9a3e6c2bd8c2fb4f09f7bbfe42f27f3853fccc60

| Command | Syntax | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Initialize repo | git init |

Creates a new Git repository in the current directory |

| Clone repo | git clone <url> |

Copies a remote repository to your local machine |

| Check status | git status |

Shows the current state of working directory and staging area |

| Stage changes | git add <file> |

Adds file(s) to the staging area |

git add . |

Stages all changes in the current directory | |

| Unstage file | git restore --staged <file> |

Removes a file from the staging area |

| Discard changes | git restore <file> |

Reverts file to last committed state |

| Commit changes | git commit -m "<message>" |

Saves staged changes with a message |

git commit --amend |

Modifies the last commit (e.g., to fix message) | |

| View log | git log |

Shows commit history |

git log --oneline --graph |

Condensed log with branch structure | |

| View diff | git diff |

Shows unstaged changes |

git diff --staged |

Shows staged vs last commit | |

| Create branch | git branch <name> |

Creates a new branch |

| Switch branch | git switch <name> |

Switches to another branch |

git switch -c <name> |

Creates and switches to a new branch | |

| Merge branches | git merge <branch> |

Merges specified branch into current branch |

| Delete branch | git branch -d <name> |

Deletes a branch (safe) |

git branch -D <name> |

Forces deletion of a branch | |

| View branches | git branch |

Lists all local branches |

| Track remote branch | git branch -u origin/<branch> |

Sets upstream for local branch |

| Push changes | git push |

Uploads commits to remote (default branch) |

git push origin <branch> |

Pushes a specific branch to remote | |

| Pull changes | git pull |

Fetches + merges changes from remote into current branch |

| Fetch only | git fetch |

Downloads changes from remote but doesn’t merge |

| Check remotes | git remote -v |

Lists configured remotes and URLs |

| Tag a commit | git tag <name> |

Tags the current commit |

git tag -a <name> -m "<msg>" |

Annotated tag with message | |

| Checkout commit | git checkout <commit> |

Switches to a specific commit (detached HEAD) |

| Stash changes | git stash |

Temporarily saves uncommitted changes |

git stash apply |

Reapplies stashed changes | |

| View staged files | git ls-files --stage |

Shows what’s in the staging area |